by Elena Dakoula

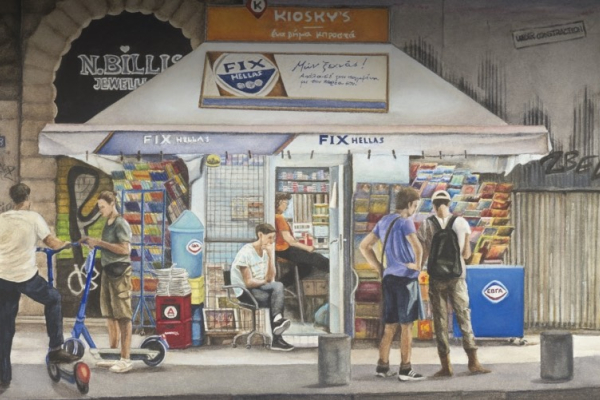

The Athenian kiosk, a familiar, living cell of the urban fabric and an inseparable part of our everyday life, is considered a worldwide originality, because you do not encounter it anywhere else in the world with the form as well as the way of operation that it has in our country. It is an exclusively Greek institution that has existed, officially, for 110 years and constitutes one of the points of reference for Greece. Due to its continuous operation, it can be considered one of the longest-lived professional sectors.

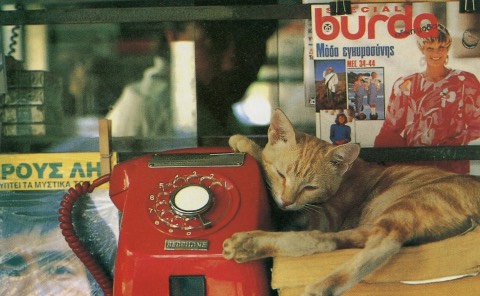

The kiosks are counted among the tourist attractions, and foreigners are impressed by these “small miracles,” as they call them, of a few square meters, that contain everything and in which one can find a beer or a small bottle of vodka at 2 a.m., something that in their countries is unthinkable.

The Athenian kiosk and its history

The roots of the kiosks of Greece are found in the small, occasional tobacco shops that appeared after the liberation in Nafplio and several years later in Athens, initially in Syntagma Square. According to the urban planning designs of the 19th century, the squares were designed in such a way as to constitute a fundamental but at the same time vital element of the neoclassical city, both for the activity and for the recreation of people. They were a meeting place, a beloved spot for the Sunday walk and a great matchmaking venue, as well as for musical events by bands that played music on elevated platforms. In Syntagma Square, small wooden decorative constructions of Swiss origin were placed, the so-called “kiosks,” which sold items of trivial value. Their form differed greatly from that of today’s kiosks. A characteristic of some of them was the conical metal roof and the limited-width polygonal floor plan.

The granting, however, of licenses and the systematic expansion of the kiosks, as the kiosks were later called, began after the Greek-Turkish War of 1897 and especially after the end of the Balkan Wars.

According to Law 254, which was voted in April 1914 following the proposal of the mayor Spyridon Merkouris, known for his remarkable action during the period of the Balkan Wars as well as for his very significant work in local government, the kiosks increased, and the Committee for the Relief of Poor Families of the War Fallen and the Disabled granted them to the war invalids.

This law received wide acceptance. The well-known columnist and poet of the early 20th century Sotiris Skipis, in an article in the newspaper SCRIPT in October 1919, congratulating the mayor for the initiative and expressing the opinion of public sentiment, wrote among other things:

“No one can imagine how many good things will immediately arise from the erection of kiosks. The kiosks will be an ornament of the city, through them many war invalids of the two wars will be served and will find a means of living. Through this means, the Greek printed matter will spread—be it newspaper, magazine, leaflet, or book. And they will be the cause for our great provincial cities to be stirred a little and imitate a little the capital.”

The kiosks, in the form of a small yellow-painted wooden booth, of dimensions 0.70 x 0.70 meters, consisting of four metal pillars, a base for placing products such as newspapers, loose cigarettes, and some rudimentary sweets, and a canopy on the top for shade, appeared in the early 20th century on the streets, squares, and parks of urban centers. They were called “periptera” (kiosks) because their form refers to an architectural type of ancient Greek temple design. Specifically, peripteros is called the temple whose naos (that is, the inner chamber where the statue of the deity is kept) is surrounded by a colonnade, the so-called pteron.

Apart from being a source of livelihood for the wounded and disabled veterans of war, there was another reason for their creation—and that was the control of the tobacco trade, which until then had been conducted by itinerant vendors and a few tobacco shops. The state granted the kiosks the exclusive right to sell tobacco products, thus creating a tax-collecting mechanism that, with minimal cost, generated high revenues. Cigarettes were the product that supported the kiosk for many decades.

In Athens, the first modern, for that time, kiosk, with the form that we know today, was set up on Panepistimiou Street in 1911.

According to the law of 1922, the Ministry of Welfare granted the exclusive use of the kiosks to the “Panhellenic Union of War Wounded 1912–1921.” According to this, the Union was the only official body that had prior approval from the Ministry of Transport, which determined the shape and size of the kiosks that were expected to be erected. They became uniform and of the same color. It was legislated that the concession was a personal matter; it was not allowed to be sold, transferred, mortgaged, or subleased. It was also permitted for a partnership only between two partners and only with the permission of the Minister of Transport. After the death of the beneficiary, the license was transferred for five years to his children or his wife. The rental fee started from 20 drachmas and reached up to 250. These revenues went to the special “Fund for the Dowries of Daughters and War Wounded.”

Omonia Square, before it began to suffer from the continuous redevelopments, was full of kiosks. Specifically, in 1930, when the underground railway station was being built, eight tall columns with statues of the Muses were erected on the square, in order to cover the openings of the air vents, and at the base of each one a kiosk was also placed.

For reasons of symmetry, one of the nine Muses was missing — Calliope. She was placed in the basement of the station, next to the public urinals. Whenever a passerby asked where the public toilets were, the answer was: “Down at Calliope.” From there, in the slang of the army, Kalliopi came to mean the chore of cleaning the toilets. And here the parenthesis closes. The aesthetic result in the square was not as expected, and thus in 1937, the Muses were taken down, but the kiosks had been loved by the Athenians, and so they remained in their place and did not share the fate of the Muses.

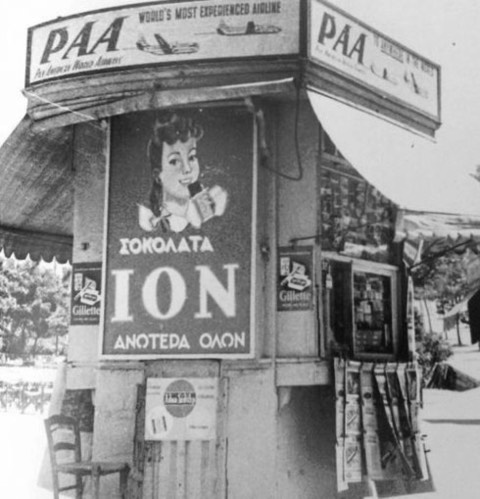

During the Interwar period, only newspapers, cigarettes, small sheets of mint-flavored gum, and a few confectionery products—mainly from the company ION—were sold at the kiosks. A little later, with the addition of the refrigerator—initially a wooden box that contained ice—the sale of soft drinks (lemonades and IBI sodas) began, and later ice creams. Today, the product codes sold at kiosks have reached 2,500.

At that time, when Europe as well as Greece were in the midst of political unrest and military conflicts, newspapers—which, depending on the events, could be printed several times a day—constituted the main means of information for citizens, who gathered daily around the kiosk to be informed and to comment on current events by reading the headlines.

A common starting point—a kiosk in a central spot of Athens—was shared by two empires that were founded in the field of commerce a few decades apart. The first case is that of Mignon, the small-sized kiosk (hence its name), which was opened in Chafteia in 1934 by Giannis Georgakas, in partnership with Angelos Serafeimidis, a migrant from America. The two friends had closed the two side wings of the kiosk and had transformed them into showcases where pens, shaving accessories, scissors, glasses, pocketknives, and other small items were displayed. From that small kiosk began the history of one of the largest department stores in the country.

The second is that of the Hondos brothers, founders of the Hondos Center chain. The five brothers started as sales representatives of soaps and cosmetics, and in the early 1960s they took over the operation of a kiosk on Omirou Street. Thanks to their special talent for commerce and with hard work, they managed in 1967 to open their first store, which was located exactly opposite that kiosk! And that was only the beginning.

A landmark year for the kiosks was 1969, since then, by joint decision of the Ministers of National Defense, Coordination, and Public Works, they increased in size (1.30 x 1.50 meters), acquired shelves, shutters, and refrigerators, and the color and advertisements on the awnings were defined. It is also worth noting that the colors red, black, and white were prohibited from being used because of the political climate of the time.

It is also certain that from the categories of citizens who were granted licenses to open kiosks, communists were excluded, since, as is known, after the Civil War but also after the fall of the dictatorship they were under persecution. And, as it is said, to this fact was owed the then-prevailing opinion that kiosk owners, along with doormen, were informers of the police.

Two years later (in 1971), by special legislation, the tenants of kiosks were recognized and acquired rights as a class of professionals. Issues of jurisdiction, use and succession were also clarified, and the list of products for sale was expanded.

In the memory of many will exist the MELO wafers with the little papers with the costumes and flags of the countries of the world or the heroes of Disney, the rooster lollipop, the milk caramels wrapped in gold paper, the pasteli (sesame bar), KOLYNOS toothpastes, ASTOR razor blades, the little packets with black hairpins, combs, Camel nail polishes, shoelaces, Algon for headaches, Tempo tissues.

And, as described in Dimitris Gkionis’ narrative “The Kiosk” by little Dimitris Koukos, who worked summers at his brother’s kiosk in the late 1950s: “Those who had money still bought Lux soaps and not Hermes, Gillette razor blades and not Astor, Colgate toothpaste and not Kolynos.”

And a little further down:

“There were also some who quietly asked for some colored little sachets or little boxes of various brands: Give me a condom, or a preservative, or by their name: an OK, a little cap, a baby one, a little fox… Often those who shopped had beside them some female who pretended not to know what her man was buying.”

As for the press, the titles of newspapers multiplied, and foreign ones appeared, because tourism had begun to develop and many tourists were now visiting Greece. From the Greek press, Athinaiki, Akropolis, Vradyni, Thisavros, Romantzo were the newspapers and magazines with the highest demand, while Gaour-Tarzan, Mikros Iros, Classic Illustrated were particularly popular with young readers.

With the same regulation mentioned above, the method for calculating the number of permitted kiosks in each municipality was determined — the quotient of the number of residents divided by 400. During the dictatorship period, kiosks were numbered. The one with number 1 was located in the center of Athens, in Monastiraki.

After 1980, other categories such as National Resistance fighters and disabled veterans of the Democratic Army were included among kiosk license holders. Local authorities allowed kiosks to cover 4.25 sq.m. with shutters and to occupy, for a fee, an additional 6.35 sq.m. of public space for two refrigerators. Thus they began to expand and gradually approach their modern form — often resembling small mini-markets, though lacking the personal character and appearance of the traditional kiosk as we once knew and loved it.

On October 3, 1997, one of the oldest kiosks on Panepistimiou Street, opposite the Arsaki Arcade, made headlines when, during metro construction works, it was swallowed by the tunnel-boring machine “Jason”, and the kiosk owner Mr. Trapezalidis and his wife were miraculously saved at the last moment.

From 2002 onward, other social groups, such as veterans of the Cyprus war or people with serious disabilities, were also allowed to obtain kiosk licenses. In 2006, kiosks were enlarged by twenty centimeters, reaching dimensions of 1.50 x 1.70 meters. Before the financial crisis, rents ranged on average from €700 to €1,300, depending on the area.

In 2012, the Ministry of Defense (which had responsibility for this business activity) decided to liberalize kiosk licenses, transferring the management of 70% of them to municipalities, on the condition that they be granted through public tender, never by direct concession, while the remaining 30% were to be given to people with disabilities and families with many children, based on income criteria. It was also legislated that the locations of kiosks would be determined by municipal council decisions in each city.

In the same year, restrictions based on population criteria, the limited number of people allowed to exploit them, and the limitation of subleasing only to natural persons were effectively abolished. This change in legislation was, in essence, the beginning of the end for many kiosks. In recent years, due to socioeconomic changes, legal reforms, and strong competition from modern mini-markets and delivery companies that distribute kiosk products through digital platforms, there has been a dramatic decline in their numbers.

According to 2013 data, kiosks throughout Greece numbered around 10,000, of which 3,500 were in Attica and 1,300 in the Municipality of Athens. Based on current figures, there are now about 6,000 kiosks nationwide, 2,500 of them in Attica and around 500 in Athens. Let us wish and hope that the kiosks will be preserved and not disappear from our cities and our lives. Apart from their practical but also cultural role—since they continue to be a kind of urban attraction—they remain a valuable, familiar, and inseparable part of our collective memory